This Is How AI Kills Progress: A Working Theory

the marvel cinematic universe, bob dylan, and artificial intelligence

What Do You Know About Movies?

The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) took the world by storm. Since it’s inception in 2008 with the record breaking Iron Man movie, the MCU has grossed nearly $30 billion dollars across 33 films. Over and over, it continues to be the franchise that consumers crave most. Voting with their dollars, movie goers have named MCU the number one — the winner takes all. And it’s not even close.

Why is that?

The broader theme of franchising — prequels, sequels, remakes, spinoffs, etc. — has taken over the film industry. Of the top ten highest grossing movies of 2022, not a single one was an original. In fact, the percentage of movies in the top 20 that follow some franchising mechanism has been aggressively on the rise.

From ~15% in the year 2000 to ~90% in 2021, is it fair to conclude that originality has been spiraling? Perhaps.

It’s important to note the technological advancements and the mechanisms for actually watching movies back in the 1990s, and what may have changed in that decade leading to a spike in the 21st century. In 2001, DVD players had more sales than VCRs for the first time in the United States. It became more enjoyable to watch a movie in at home since the quality was substantially better, and it became easier to distribute said movies to said homes because of the new technology. The widespread distribution makes way for word-of-mouth advertising, which leads to an increased concentration of movie watchers across fewer movies.

With all that being said as a possible explanation to the graph above, it’s tangential to the primary, more soul-touching point that I’m trying to make. People flock to franchises because they’re easier to watch. You know what you’re going to get, and it’s easier to get excited over a world you can already imagine. You walk into a Marvel Cinematic Universe movie at an AMC and you know ahead of time that you’ll be able to (respectfully) turn your brain off. The stagnation of imagination is attractive because it’s just… easier.

Kyla Scanlon has written eloquently about this idea in her Nostalgia Cycle Loop theory. She says:

The nostalgic content being churned out via movies, books, even music(!) requires less imagination on our part because it comes from already-established world building. It’s easier to imagine the context around a new Star Wars or Marvel sequel when we’ve already seen what Tatooine looks like or know what Loki thinks of Thor. It’s easy.

Just like it’s easier to not go to the gym or out for a run, it’s easier to not exercise our imaginations when given the option. And, like all virtues, hope requires practice - we risk our ability to hope when we let our imaginative muscles atrophy. The inability to hope is a spiritual problem, but it can extend to a very visible economic reality, too.

So why is the Marvel Cinematic Universe the highest grossing franchise? Maybe, partly, it’s because of how easy the movies have become. I guess you could call this “watchability”, maybe it nostalgically reminds you of a childhood reading comic books, maybe you had a long day at work and don’t want to think, maybe “watchability” is just ease.

He Not Busy Being Born is Busy Dying

What we consume can change us individually, and what we create can change all those who consume it, for better or for worse, of course. But it seems to be that when we create good and forward-looking content as a society — whether it be through movies, music, or writing — the world around us changes for the better. The more that individuals succeed in their creative pursuits, in chasing true creativity, the more that those on the receiving end stand to benefit.

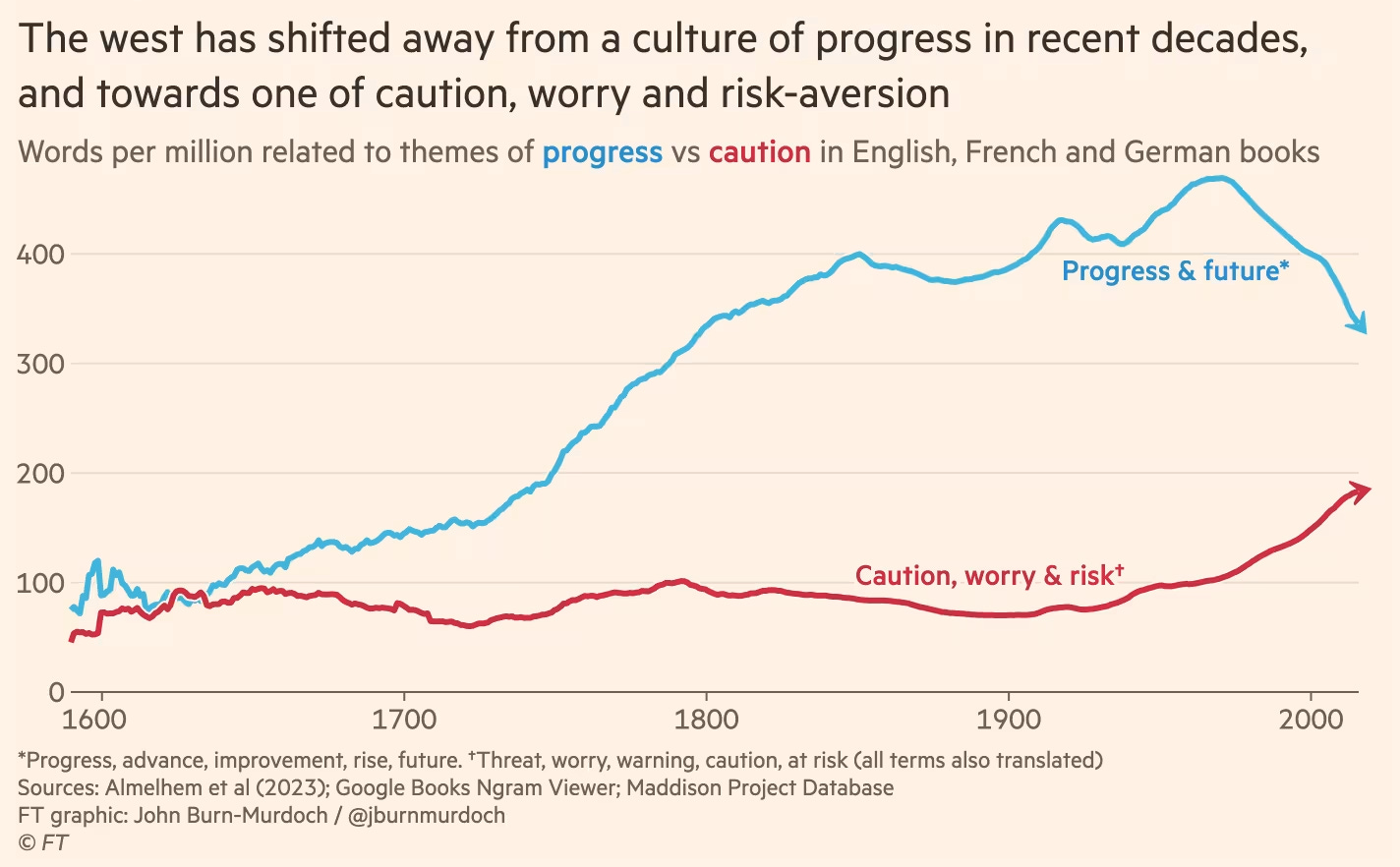

My favorite analysis of 2024 so far has been on the subject of words, and more broadly, cultural content. John Burn-Murdoch from the Financial Times analyzed millions of books that were digitized by Google to determine trends in the “frequency of words related to progress”. The result is that GDP growth has trended alongside the amount of words related to progress per million words written. You might think, “Hmm, if a country is doing well it would make sense that the people who comprise it would have more positive and progress-inducing things to say.” But that’s not really the case, from Murdoch himself:

It’s not just that people talk more about progress when their country is moving forward. In both, culture evolved before growth accelerated.

We see these trends play out in Britain and Spain, but perhaps more interesting to note is how words have trended more recently. Again from Murdoch:

Extending the same analysis to the present, a striking picture emerges: over the past 60 years the west has begun to shift away from the culture of progress, and towards one of caution, worry and risk-aversion, with economic growth slowing over the same period. The frequency of terms related to progress, improvement and the future has dropped by about 25 per cent since the 1960s, while those related to threats, risks and worries have become several times more common.

Creativity in a positive light, quite literally, is progress. The more that a society talks about progress and prosperity, the closer it gets to it. But over the past several decades, we’ve seen the tides turn, much like we’ve seen the tides turn in movie originality! Again, that’s not to say that there aren’t new and creative movies being produced, it’s just to say that as a society, we haven’t been voting for those movies to top the charts with our own dollars.

There’s a lot behind this, obviously, but I think we see these trends for two reasons:

The mechanisms by which we acquire capital have favored nostalgic elements of society at an increasing rate. Ever-growing corporations know that another Marvel movie will bring in the big bucks, and that can detract from the elements of progress that we as a society would like to see, perhaps we don’t know we’d like to see it.

Negativity drives consumption. Readers are more likely to click on negative headlines, and the smallest difference in clickthrough rate can lead to millions of dollars for those publishing the content. Unfortunately, it pays to be negative, it pays to fear monger, it pays to kill the vibe.

The issue we run into is when these twisted incentives of the internet stand in the way of real progress. As we know from Murdochs analysis, it’s not unreasonable to say that the content thrown into social spheres has great influence, not only as a reflection of the present, but as an indicator for the future.

The more we see the same content being churned through the money making machines, the more we’ll see a decline in progress, at least progress towards a healthy and positive society.

In Bob Dylan’s hit song “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding”, he sings “He not busy born is busy dying.”

In the most Bob Dylan verbiage, and along the same lines, he’s quoted with saying:

An artist has got to be careful never really to arrive at a place where he thinks he’s at somewhere. You always have to realize that you’re constantly in a state of becoming. As long as you can stay in that realm, you’ll sort of be alright.

The words we write tell us that we are moving away from words of progress, away from words of becoming, and trending towards words of caution. Why should we pay any attention to this? Well, I think we’re entering a new paradigm as our lives becoming increasingly influenced by artificial intelligence. These AI models need data to train on. Inevitably the most relevant data, particularly for text-to-speech and text-to-video models, will be the most recent data, which is sad, lackluster, nostalgic, progress-lacking data. (Apologies for being dramatic here)

Not to linger on Bob Dylan for too long, but one last quote, “Nostalgia is death”, from an interview many years ago.

Enter Artificial Intelligence

Earlier this year, OpenAI released Sora — an AI model that can create incredibly realistic videos from a simple text prompt. The videos are astonishingly good, especially considering that this is OpenAI’s first demonstration of a text-to-video model. You ask the model to create a video of puppies playing in the snow, and it returns to you just that. Alongside the construction of Sora was, of course, the developments of GPT-4, possibly the hottest product released last year.

Despite how good the models have gotten, AI companies are running into an issue. The demand for good data is on the rise, the demand for data centers is on the rise, and companies are running out of data to train their models on.

A large part of what the AI researchers spend their time on is determining how to improve models with the same data they currently have, or even with synthetic data generated by the companies themselves.

Deepa Seetharaman from the Wall Street Journal writes:

One strategy used by DatologyAI, the data-selection-tool startup, is called curriculum learning, in which data is fed to language models in a specific order in hopes that the AI will form smarter connections between concepts. In a 2022 paper, DatologyAI’s Morcos and co-authors estimated that models can achieve the same results with half the data—if it is the right data—potentially lowering the immense cost of training and running large generative AI systems.

Data availability is becoming an issue as these companies plunder the entirety of the internet with the goal of providing better inputs to their models. They are searching every corner of the internet that they can get their hands on. In 2023, OpenAI partnered with Shutterstock on a six year deal giving OpenAI the ability to train their models on Shutterstock data. Access to millions of images and videos on the Shutterstock platform has proved to be incredibly valuable to OpenAI. This deal was done entirely on the basis of DATA!

Furthermore, data centers are not easy to build, especially given the recent demand boom. Again from the Wall Street Journal, Tom Datan writes:

The lead time to get custom cooling systems is five times longer than a few years ago, data center executives say. Delivery times for backup generators have gone from as little as a month to as long as two years.

Sam Altman, founder of OpenAI, is trying to raise TRILLIONS (!!) of dollars to bolster supply chains for chips and data centers.

But the aggressive search for data is not without consequence, and there are a few questions I’ve been thinking about through this AI craze:

What does this endless search for data mean for the companies building the product and for the customers using the product?

To what extent will these AI model feed the Nostalgia Cycle Loop and the online proclivity for negativity, with the sole intent of producing more capital, widening margins, and recycling already-proven content?

For the sake of brevity, I won’t delve too deep into the first question. However the second is a matter that will greatly influence culture in the years to come.

As these models grow in robustness, perhaps they’ll learn that the easiest cultural components to profit off of are those that are not forward-looking or progress driven because both 1) society has shown demand for that kind of stuff (prequels, sequels, etc.) and 2) the content would be easier to produce from an AI perspective as there is more guidance on how to write the script for another Marvel movie than there is to conjure up the idea for a groundbreaking film.

The words we use matter, the content we create matters, and if these astounding artificial intelligence models begin to cycle content, we could see the end of progress. We could see the stagnation of words. Returning to Murdoch’s analysis from above, one of the worries around AI generated content becomes a possible lack of terms related to progress, because that doesn’t make any money. These models are smart enough to know that they can prey on nostalgia, and soon they’ll be smart enough to write their own movies, their own music, to generate their own photos. That’s MY worry — that originality goes out the window, that scripts and lyrics and visuals are reused, and that this type of content can be cranked out so quickly that it takes over the internet.

I know this theory requires a lot of imagination, particularly with regards to a future surrounded by artificial intelligence that is quite difficult to picture. But it feels like we’re moving too fast — that there aren’t enough guardrails around what content can be generated by artificial intelligence and how that content can be distributed to the world. Again, as the title states, it’s a working theory. It’s based on gut more so than rigid data. But I think the content we consume is unbelievably important, and we spend more and more time in front of screens each year. One can only hope it’s not a snowball effect, that we don’t blink and all of a sudden live in a world where the majority of our content is AI generated — that could very well end an era of progress.

Hope you’re doing well, and as always thanks for reading.

Loved this bro!! Phenomenal insights throughout. Do you see originality as something that can be cyclical like other aspects of history & culture?? Where we tamper with moving so far ahead that eventually we begin to regress to older traditional methods & needs ??? Just as much as we’ve seen these big box office movies get squeezed to death for $, I feel like we’ve also seen major demand and celebration for some of the original, lower budget indie films more than before as well. But seems the data shows otherwise. Either way, what people consume (music, movies, books, video games, tv etc) absolutely effects who they become, how they behave, and how they see the world & others - without question - and it’s something that’s not talked about nearly enough. Good shiii!!! Look forward to reading more